The Protégé

Simon Ghraichy, Jeffrey Epstein, and the fog of art

Update (11. February 2026): A newly-discovered email would suggest that Jeffrey Epstein originally introduced Simon Ghraichy to Leon Botstein in June, 2014.

Pianist Simon Ghraichy’s last project with Deutsche Grammophon was a standalone single of Philip Glass’s “The Fog of War,” released on March 11, 2022. It was one of many conflict-connected recordings that came in the weeks following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and Ghraichy drew that connection in an Instagram post announcing the release:

“‘The Fog of War’… has been composed for a documentary with the same name tracing the life of an American officer from WWII until [the] Vietnam war. Today, names change, locations too, but the fact is we still live in a world torn apart with war, power and conquest: WWII, Cuba, Vietnam, Lebanon, Israel, the Gulf and today Ukraine… there has always been an assaulter and an assaulted, and particularly millions of innocent souls perishing - collateral damages. Today, I dedicate this music to them.”

Ten years earlier, the French pianist (of Mexican-Lebanese heritage) was a relative unknown. A major breakthrough had come in 2010, according to some versions of his biography, “after an enthusiastic review by journalist Robert Hughes in the Wall Street Journal.”1 The following year, he released his first album, Always in Motion: Opera Transcriptions and Paraphrases by Franz Liszt.

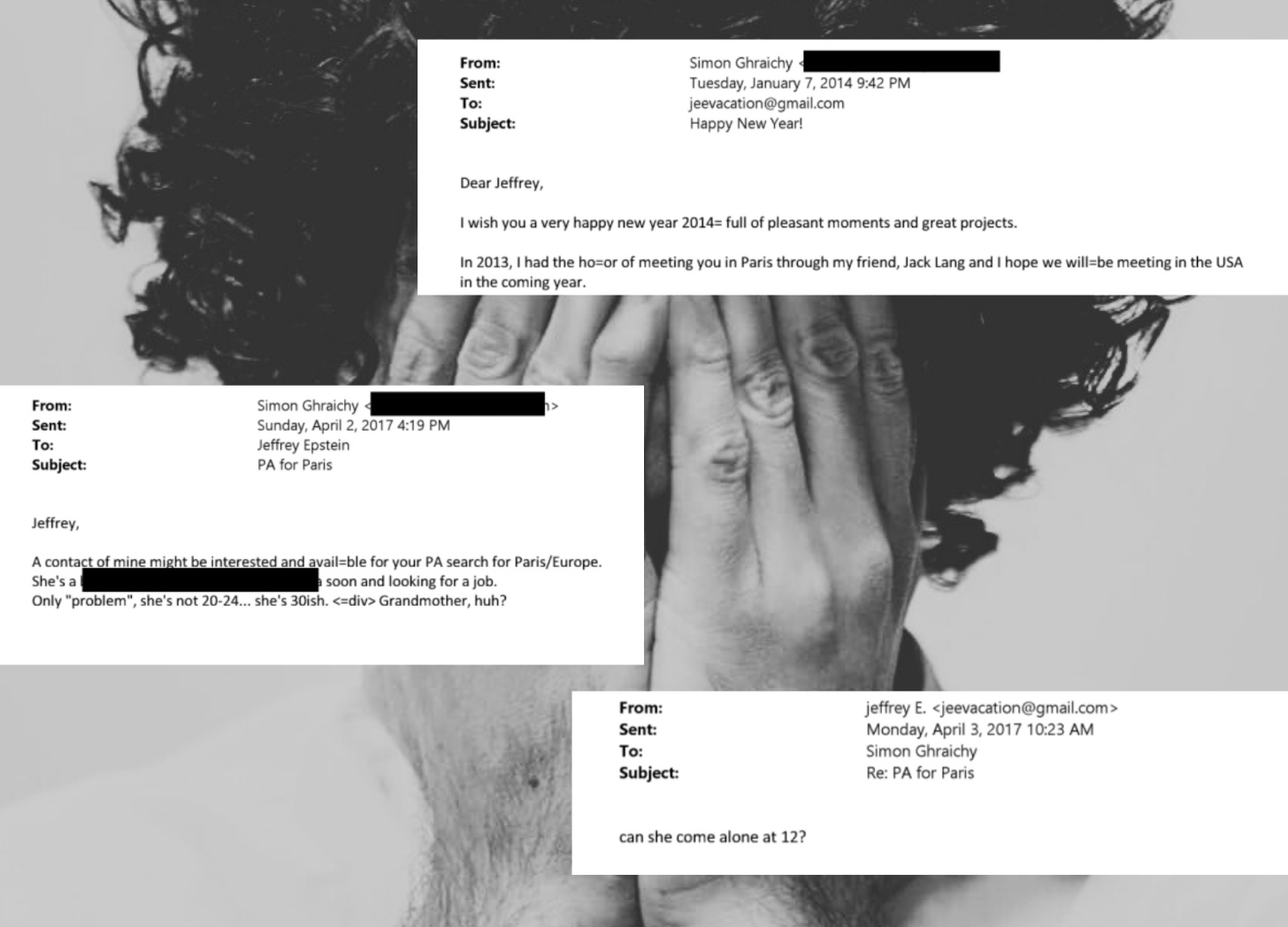

And in 2013, he met Jeffrey Epstein. The introduction apparently came via a mutual friend, French politician Jack Lang (who, on Saturday night, resigned as president of Paris’s Institut du Monde Arabe). “I hope we will be meeting in the USA in the coming year,” Ghraichy wrote to Epstein at the beginning of 2014.

In fact, Epstein appears to have become something of a professional mentor to Ghraichy beginning in that year, particularly after a meeting that the two had on September 14. That same day, Epstein sent a flurry of emails regarding the pianist, including several to conductor Leon Botstein: “I think Simon needs a local manager, ideas? He’s here for ten more days?”2 reads one. Another, sent 20 minutes earlier: “When will you decide the Simon Graichy [sic] piece.”

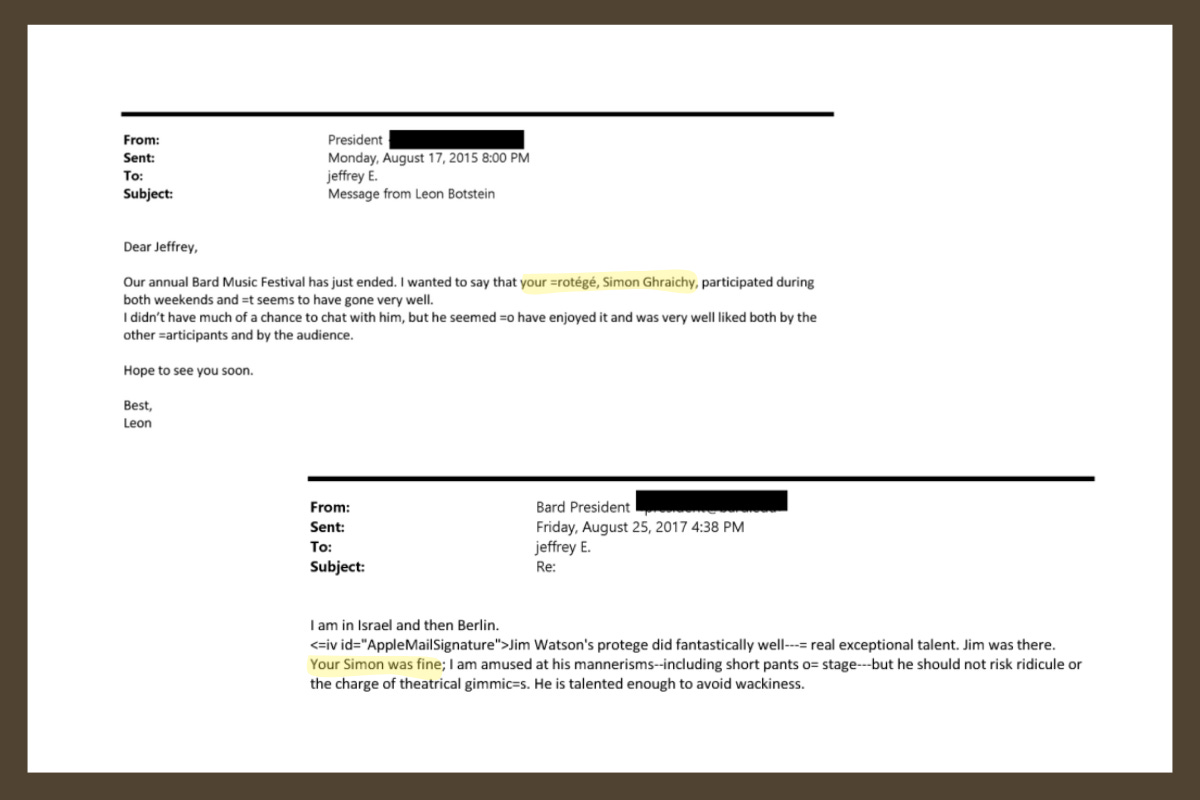

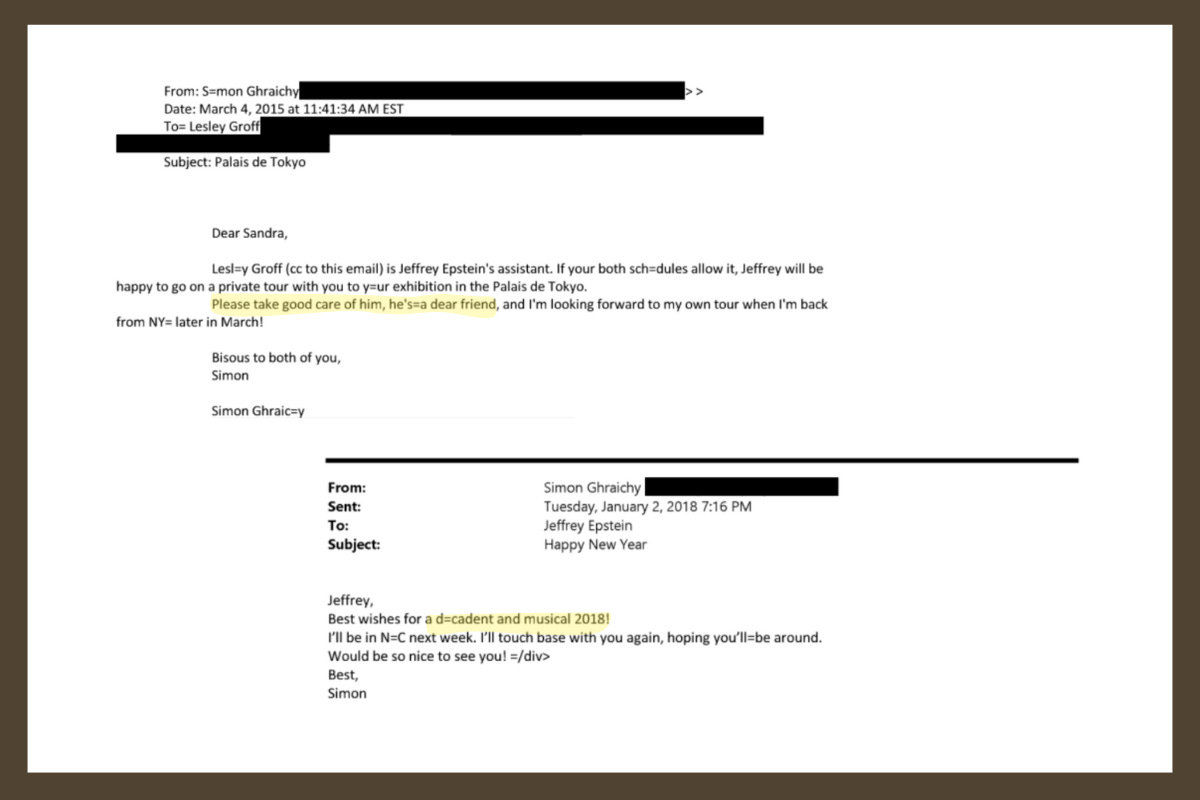

In response to the second email, Botstein replied: “Will decide in a month or so but he will be asked to reserve time on the two weekends in August.” In August of 2015, Ghraichy performed on both weekend programs for “Carlos Chávez and His World” at the Bard Music Festival—which runs under Botstein’s co-directorship. “Your protégé, Simon Ghraichy, participated during both weekends and it seems to have gone very well,” Botstein reported back to Epstein on August 17.

“Protégé” was a word that Botstein used more than once to describe Ghraichy in relation to Epstein and, at least in the professional sense, it’s apt. Also following his September 14 meeting with the young pianist, Epstein began to reach out to his network of contacts to help Ghraichy find “a local manager.” Botstein in turn wrote to his executive director at the American Symphony Orchestra, Lynne Meloccaro.

“It is really hard to get good representation these days,” Meloccaro wrote back to Botstein that month, but compiled a list of “mostly veterans in NY and Europe who might be willing to talk with Simon and point him in a helpful direction.” Epstein also asked an unnamed associate to “ask Josh Bell who manages him.” That contact reached out to Joshua Bell’s assistant via a mutual friend, ultimately asking for an introduction to IMG Artists. (This lead also seemed to have gone cold very quickly, according to the available files from Epstein’s emails.)

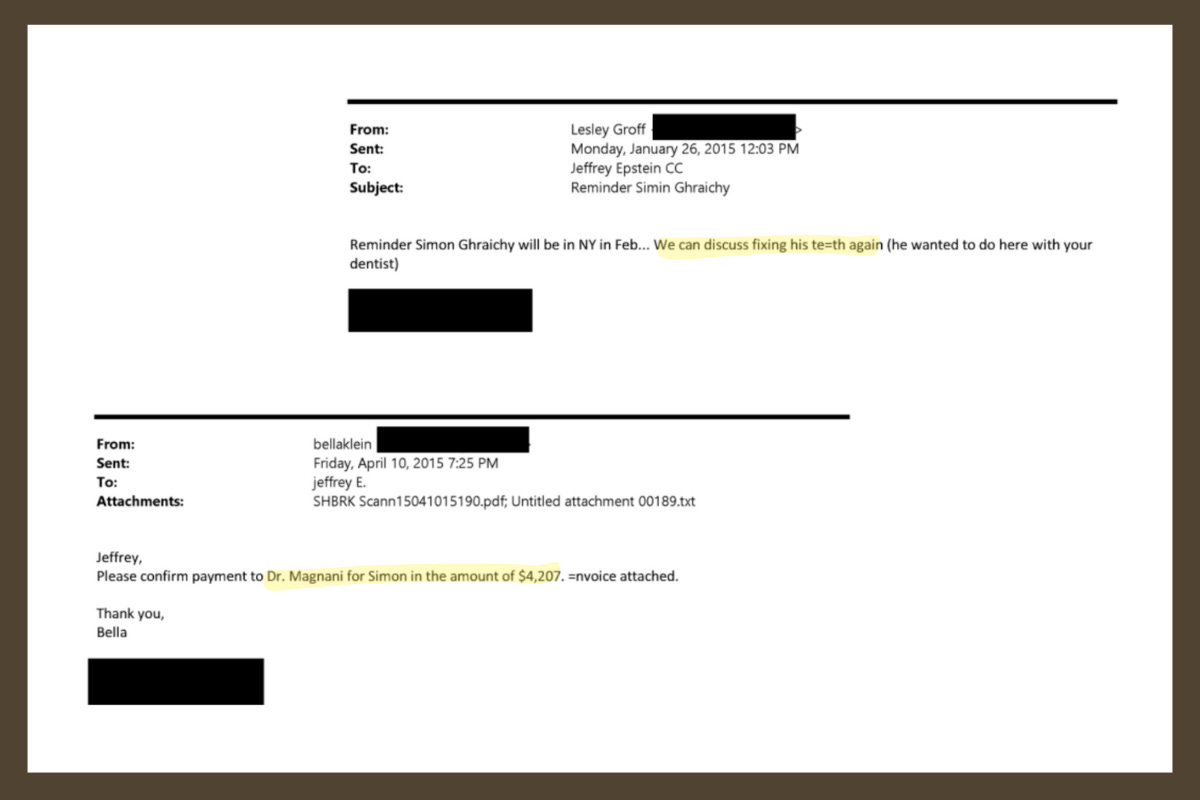

Finally, that September, Epstein also seemed to suggest that Ghraichy fix a cosmetic flaw with his front tooth out of consideration for his image. Ghraichy followed up on this with Epstein’s assistant, Lesley Groff, later that month, saying: “I don’t even notice it anymore, and people around me [think] of it as a sign of ‘identity’ (like a scar on the cheek or whatever…), but if [Jeffrey] thinks it should be better fixed for my image and career, then…who knows!” The following year, Epstein introduced Ghraichy to his own dentist in New York and agreed to pay $4,200 for dental work.

At the same time, Ghraichy’s career began to reach the next level. He made his debuts with the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence and Carnegie Hall in the second half of 2015, and both his Kennedy Center and Berliner Philharmonie debuts in 2016. He also signed an exclusive recording contract with Deutsche Grammophon that year, telling the Huffington Post: “After I’ve put my autograph on that contract, here we are celebrating my signature with the staff at Universal Music [DG’s parent company]. It feels so good to be surrounded by professionals from the most prestigious music industry. And yet, they’re all young and bright and sexy!”

The extent of Epstein’s influence in these specific advances is murky. Archive.org captures of Ghraichy’s website from 2012 to 2016 don’t indicate any shift in management or public relations, especially in the United States. Nor was Ghraichy a unique case; Epstein offered similar forms of financial and networking support to other musicians, introducing one violinist to Itzhak Perlman and paying for several young musicians to attend Juilliard. These musicians, however, were generally female—at least one subsequently reported that the interest Epstein took in her career (beginning when she was 13 years old) was a front for grooming her. More rarely did he do favors for male musicians, and usually there was a clear benefit to them, such as the $165,000 cello he purchased for Yoed Nir, the son-in-law of former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak.

Regardless, one key benefit of having someone like Epstein in your corner at such a tender stage in your career goes beyond money. His reputation at the time as a rogue-genius financier and philanthropist, by design, overshadowed his previous criminal record for solicitation of prostitution and solicitation of prostitution with a minor. It also offered access as a form of soft power to the young cultural aspirants that Epstein chose to mentor. His 2014 emails with Botstein appeared to at least put a powerful thumb on the scale for Ghraichy making his Bard debut (a prestigious festival that draws several major critics to Annandale-on-Hudson each summer; he also returned to the festival in later seasons). The list that Meloccaro compiled for Ghraichy included several well-known potential managers, including those who at the time worked with the likes of Fazil Say, Piotr Anderszewski, and Jan Lisiecki.

Epstein would also appear to be the link that facilitated a meeting between Ghraichy and film director Woody Allen: On October 5, 2015, Ghraichy posted a photo of himself with Allen to his Instagram (a post that was seemingly deleted after I wrote to Ghraichy for comment to which, as of this writing, he has yet to respond). “Enjoyed so much playing piano for you in such a small VIP comitee [sic] and beautiful place,” Ghraichy wrote in the caption. The previous evening, he had met with Epstein at 5:00pm, two hours before Allen and Soon-Yi Previn were scheduled to have dinner. While Ghraichy’s post doesn’t specify a date that he met the director, the background of the photo matches some of the interior details for Epstein’s Manhattan townhouse (notably the unique wood and gold paneling on the bookshelves and the blue damask wallpaper).

As Ghraichy noted in 2022, The Fog of War is a documentary scored by Philip Glass and directed by Errol Morris. The title refers to a known condition of confusion and poor judgment made amid the chaos of warfare, and is something invoked by the film’s subject, Robert McNamara, who served as the United States Secretary of Defense under both Kennedy and Johnson.

Morris structures the film around ten theses or lessons. These, in turn, are gleaned from hours of interviews with McNamara, whose analysis of bomber commands during World War II ultimately led to General Curtis LeMay’s low-altitude firebombing raids of Japan for maximum damage3, and whose tenure as Secretary of Defense spanned the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Bay of Pigs, and eight years of the Vietnam War—including a leading hand in Operation Rolling Thunder, which killed between 30,000 and 65,000 civilians.

By 1968, McNamara had either resigned or been fired by Johnson (although if you have to ask it’s probably the latter) and spent the rest of his life on a sort of apology tour. He did this in large part through his own forms of soft power and cultural influence, embracing a second act in international development, publishing a memoir, returning to Vietnam in 1995, and participating in The Fog of War, which earned a 2004 Academy Award.

As a result, there’s a sense of moral outsourcing in the film that Glass captures in the quiet detachment of his score (particularly in the three-and-a-half minute version recorded by Ghraichy). It speaks to the aloofness of McNamara’s own reflections on actions that he himself described as war crimes, and his preference to lay the main responsibility of Vietnam at Johnson’s feet. As Amy Davidson Sorkin wrote in the wake of Morris’s 2009 death for The New Yorker:

“Robert Strange McNamara was often described as ‘haunted’—the Times, the Washington Post, and Reuters used the word in their obituaries, as did any number of others. But which ghosts were doing the haunting? Those of the young Americans whom he sent to Vietnam? Of the many more Vietnamese, of all ages, who died in a war he designed and (while it mattered) defended?”

It’s impossible to tell, in part because McNamara, haunted as he may have come off to others, was also seemingly disinterested in exorcising those ghosts. “What makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?” he asks rhetorically of his hand in the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. Later, of Vietnam, he says: “I never in the world would have authorized an illegal action. I’m not really sure I authorized Agent Orange; I don’t remember it. But it certainly occurred, the use of it occurred while I was Secretary [of Defense].”

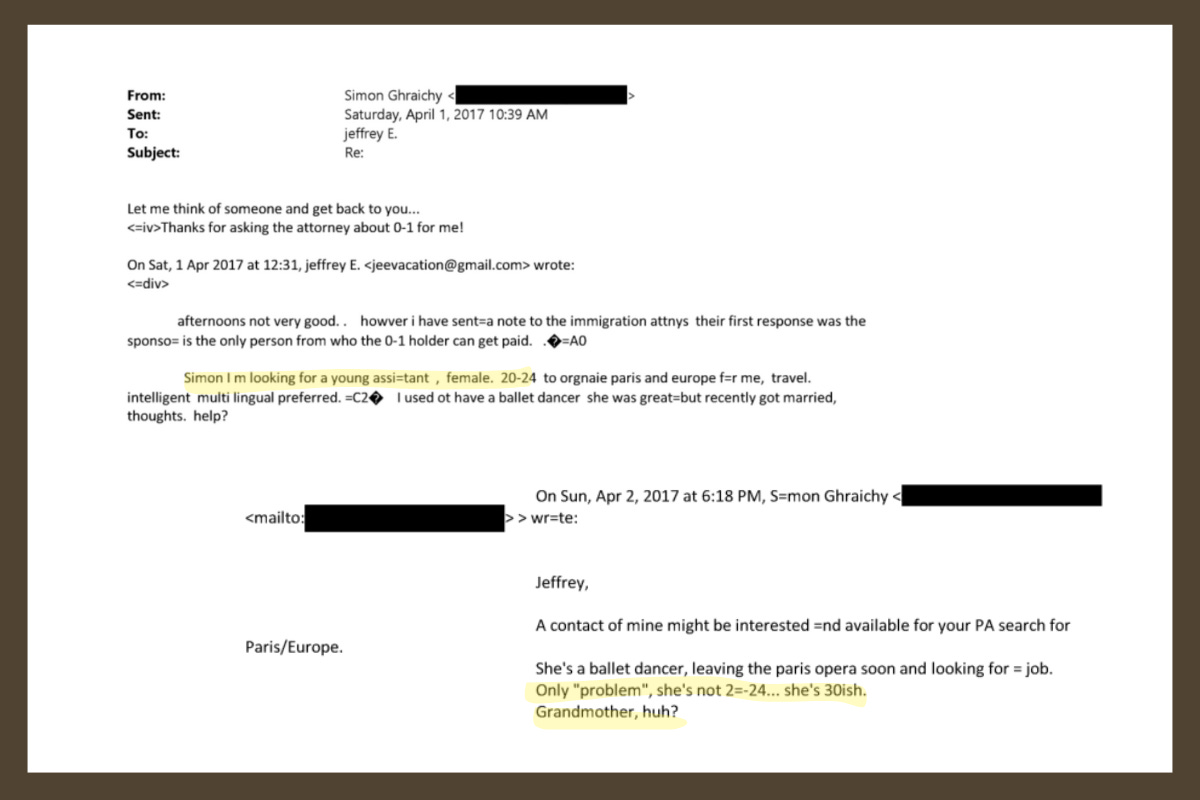

In April 2017, a few months after his debut album with Deutsche Grammophon was released, Ghraichy received an email from Epstein. After mentioning some matters relating to Ghraichy’s O-1 visa, Epstein wrote:

“Simon I’m looking for a young assistant, female, 20-24 to organize Paris and Europe for me. Travel. Intelligent, multi-lingual preferred.… I used to have a ballet dancer. She was great, but recently got married. Thoughts. Help?”

In previous years, Ghraichy consistently reached out to Epstein with offers of free tickets to his own concerts—including his two Carnegie Hall performances.4 He also offered up tickets to others, particularly at his home base in Paris. This, however, was the first favor that Epstein asked of Ghraichy, who responded the next day with a potential lead—another ballet dancer who was about to leave the Paris Opera. “Only ‘problem,’” he added, “she’s not 20-24…She’s 30ish. Grandmother, huh?” He offered to bring the woman to meet with Epstein, who wrote back: “Can she come alone at 12?”

Upon learning, however, that Ghraichy didn’t know the woman well or her level of English proficiency, he changed his mind. “Keep looking,” he wrote on April 3. A separate email thread discussed another possible, trilingual, candidate (the acquaintance of a Russian photographer), but without any clear resolution.

These exchanges bear a similarity to one Epstein had with French composer Frédéric Chaslin in 2013, in which Chaslin recommended a 21-year-old philosophy student who “looks a little like Roman Polanski’s current wife.” Last week, Chaslin clarified that the contact was for an American translator to accompany Epstein to Parisian museums, telling the Violin Channel that he felt “complete solidarity with the genuine victims of Jeffrey Epstein,” and that he considered himself “a collateral victim” in the matter.

One line that struck me from Chaslin’s statement, however, came earlier on, when he said that his own email exchanges with Epstein (from 2013 to 2019) “took place in a context in which he was, at the time, widely perceived in international cultural and artistic circles as a potential arts patron.” It’s a familiar talking point, one invoked by Botstein in 2023 when he told the New York Times: “Among the very rich is a higher percentage of unpleasant and not very attractive people.” He reiterated that position last week after his ties to Epstein were more fully codified in the most recent release of documents from the Justice Department.

I’m loath to compare potential war crimes to objectifying young women via email—even if those emails are sent to Jeffrey Epstein.5 Yet this idea of cultural capital is a throughline; in both contexts, it’s how people in power (and many people in their orbit) are able to insulate themselves from consequence.

In an epilogue to The Fog of War, McNamara snaps at Morris: “I don’t want to add anything to [the discussion of] Vietnam. It is so complex that anything I say will require additions and qualifications.” How often is “complex” invoked as a reason for separating art from the systems that fund it? How often is music invoked as the form that rises above complexity and politics?6 The lesson that young aspirants are taught, especially if they don’t have generational wealth, ready-made connections, or basic dental care, is to hold their nose.

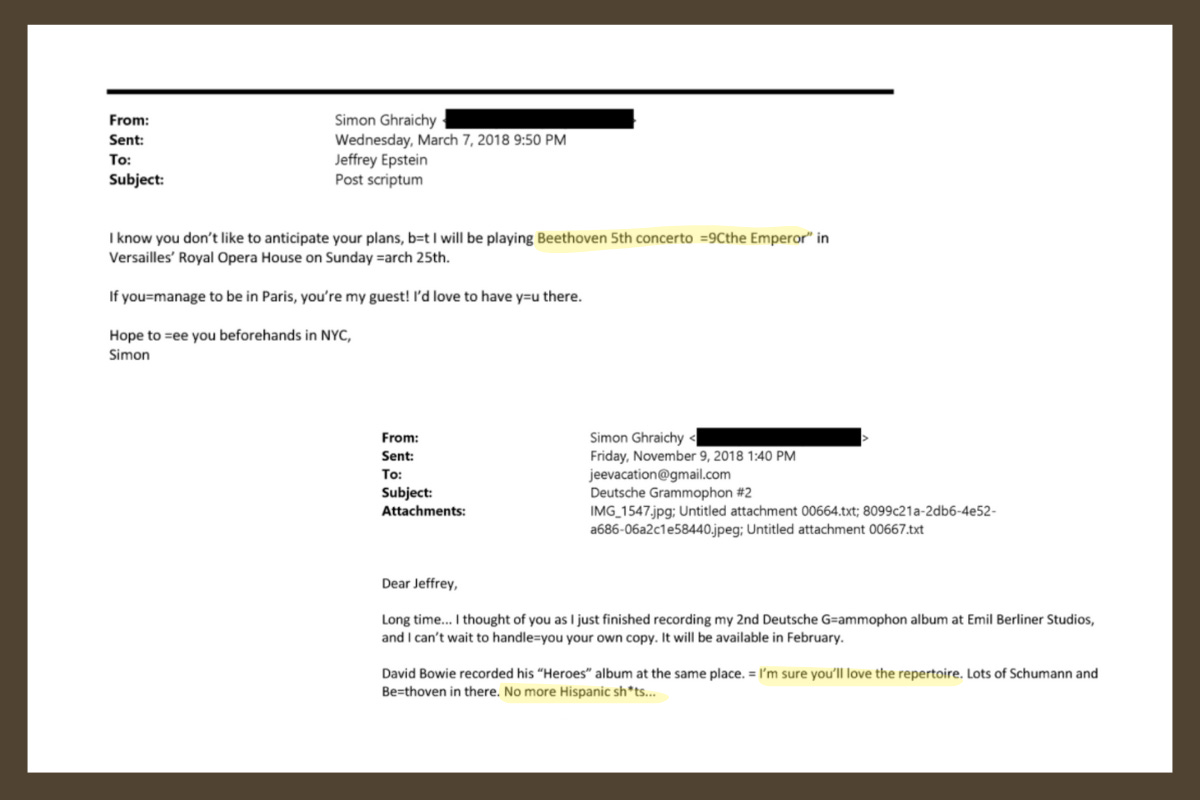

Early in his career Ghraichy also proved dedicated to Latine and Hispanic composers, to whom he felt a kinship through his Mexican heritage on his mother’s side. “Latin American music is flowing in my veins,” he said in an early artist biography. The repertoire was also the foundation of his Carnegie Hall recital debut. “They immediately think it’s going to be less ‘genius’ [compared to what] a European composer must be,” he told NY1 in 2015. “But then when they listen to the music, after they’ve heard the pieces, you can immediately see them—the change on their faces—and they have been convinced.”

One person not convinced was Jeffrey Epstein, according to several emails throughout his mentorship of Ghraichy. The last mention of this came in November 2018, when Ghraichy told Epstein about his second album for Deutsche Grammophon: “I’m sure you’ll love the repertoire. Lots of Schumann and Beethoven in there. No more Hispanic sh*ts…”

“Great,” responded Epstein. “Look forward to it.”

I first saw The Fog of War at a small independent movie theater off of Lincoln Center in 2004, as a freshman playwriting major at Fordham. The man I was seeing at the time was in his late 40s, perhaps early 50s, and convinced me to skip class to go to a matinee on what was, for him, a slow workday. He sold me on the basis of Glass’s score.

At the time, the music left me with a churning sense of dread, particularly in one scene where Glass’s score pulsed against a sequence of title cards that compared the cities destroyed in Japan during World War II—some with the help of McNamara’s analysis—to cities of comparable size in the United States. By the time McNamara claimed he didn’t know anything about his authorizing the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam, I wanted to throw my popcorn against the screen. My rage boiled over when he called any further discussion of Vietnam too complex, especially as a Syrian-American who had serpent the last year watching the United States shock-and-awe the Iraq over mythical weapons of mass destruction.

The man laughed, condescendingly. “You’ll feel differently when you’re my age,” he said. I hated him in that moment. I didn’t like him that much to begin with, but being a broke college student living in New York and enjoying classical music was a fatal combination, financially. I didn’t fully realize this power imbalance at the time, but I at least knew instinctively that the only response was to smile and say nothing.

Previously on Jeffrey Epstein…

Of Course Jeffrey Epstein Was a Beethoven Fan

On November 6, 2016, banker and author Robert Lawrence Kuhn received a birthday email from financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Kuhn was surprised — Epstein had beat even Kuhn’s own family in wishing him many happy returns of the day.

“There Is a Reason You Are Still Struggling and it Is Not Your Talent”

“I don’t know what’s more unforgivable: that conductor and long-serving Bard president Leon Botstein accepted money from Jeffrey Epstein, or that he put me in the position of agreeing with American conservative outrage-monger Dinesh D’Souza.”

It was actually a post from Hughes’s column for the now-defunct website Classical TV.

Quoted emails from the Epstein files may have been edited for spelling and formatting, where necessary for clarity.

One scene in Fog has McNamara rationalizing that LeMay lost one wingman due to the risk of flying at a low altitude, but in exchange “we destroyed Tokyo.”

Epstein was at the first Carnegie performance, but missed the second. “all the girls can go if they like,” he told Groff. One redacted attendee wrote after the concert, “The best part was pretending that none of the girls know each other ahah.”

Hell, he was friends with war criminals, too.

“Music is a universal language that transcends borders, uniting people through creativity,” said Paul Pacifico, the CEO of the Saudi Music Commission, in a September 2025 press release related to a MoU signed between the SMC and the cash-strapped Metropolitan Opera.

Your writing on this subject since the latest document dump has been stellar!