Of Course Jeffrey Epstein Was a Beethoven Fan

The complicitous silence of cultural capital

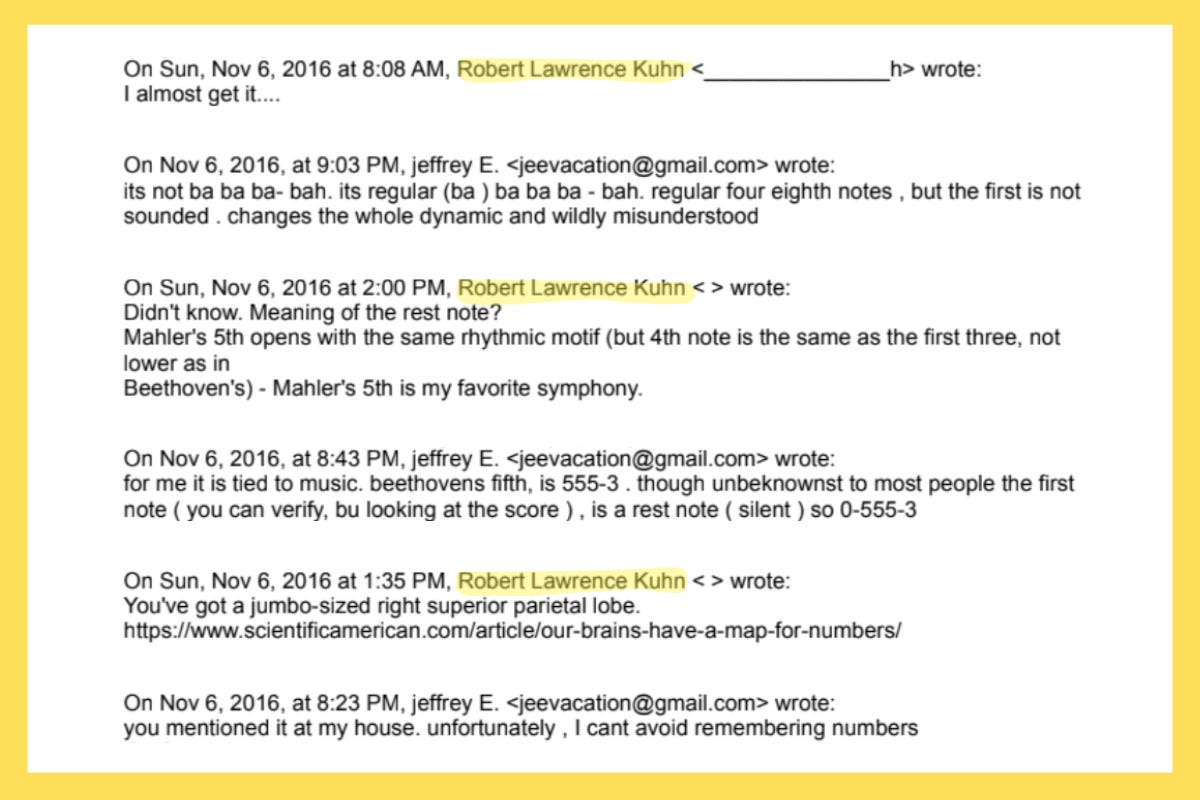

On November 6, 2016, banker and author Robert Lawrence Kuhn received a birthday email from financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Kuhn was surprised — Epstein had beat even Kuhn’s own family in wishing him many happy returns of the day.

“I cant [sic] avoid remembering numbers,” Epstein explained.

“You’ve got a jumbo-sized right superior parietal lobe,” Kuhn replied, linking to a Scientific American article. And then, somehow, things got weirder.

“for me it is tied to music,” Epstein responded in his lazily-punctuated and typo-ridden style. “beethovens fifth, is 555-3. though unbeknownst to most people the first note (you can verify, [by] looking at the score), is a rest note (silent) so 0-555-3.”1

Kuhn wrote back: “Didn’t know. Meaning of the rest note? Mahler’s 5th opens with the same rhythmic motif (but 4th note is the same as the first three, not lower as in Beethoven’s) - Mahler’s 5th is my favorite symphony.”

Epstein explained: “its not ba ba ba- bah. its regular (ba) ba ba ba - bah. regular four eighth notes, but the first is not sounded. changes the whole dynamic and wildly misunderstood”

“I almost get it…” Kuhn replied.

The 20,000+ pages of documents recently released by the Epstein estate give us some glimpses of the role that art played in his world. Much editorial space has been devoted to how Jeffrey Epstein laundered his reputation through philanthropy. His donations to institutions like MIT and Harvard gained him entry into elite circles of academics, scientists, and technocrats, and he quickly placed himself at the center of these circles as the moneyed savant. “He came to prominence in the 1990s, as the modern meritocracy was taking shape in the collision between the cult of technology and the burgeoning class of billionaires,” Gabriel Sherman wrote in a 2019 article for Vanity Fair. These billionaires, like Epstein “wanted to certify their own genius by conversing with other geniuses.…Science was sexy, a way to beat the markets.”

Art, by contrast, was the underbelly to a science-led meritocracy. If science was battling the markets, art was the spoils of that war. It legitimized the victor through the right investments at auction and the right references dropped in emails with other powerful men. Indeed, the first allegations against Epstein came from an art-world connection. A board member of the New York Academy of Art from 1987 to 1994, Epstein met student Maria Farmer in 1995 and hired her as a sort of art advisor. The following year, Farmer went to both the NYPD and FBI with complaints that Epstein had assaulted both her and her teenage sister, to no avail. She had a similar experience in 2002 when discussing her experience with Vanity Fair.

The subsequent Vanity Fair profile (which ran in 2003 without any mention of Farmer) was part of an oblique publicity tour that Epstein made via a series of prestigious magazine profiles that helped to curate his reputation as an intellectual and cultural sophisticate (as well as a man of mystery — most profiles were published without ever interviewing their subject). “As some collect butterflies, he collects beautiful minds,” wrote Landon Thomas, Jr. in a semi-fawning New York magazine article from that year. Of the subject’s early career teaching math at Dalton in the ’70s, Thomas described him as “something of a Robin Williams–in–Dead Poets Society type of figure.”

Around the same time that Epstein was teaching at Dalton (in what one former student described less as Dead Poets Society and more as “sleazy polyester pants”), French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu was formulating a theory around how power was maintained in contemporary, capitalist society. “The task of legitimating the established order does not fall exclusively to the mechanisms traditionally regarded as belonging to the order of ideology, such as law,” he wrote in 1972’s Outline of a Theory of Practice. Law had long since taken a backseat, with controlling the means of production resolutely behind the wheel.

Bourdieu clarifies, however, that while business was in the driver’s seat, cultural capital had its hand on the clutch. Power was the domination of both the markets and the discourse. “The most successful ideological effects,” he concluded, “are those which have no need of words, and ask no more than complicitous silence.”

Epstein, whose working-class backstory always paled under the light of scrutiny, understood the value of cultural capital. Like so many other masters of the universe before him, he kept a hand in the world of art, including music. He claimed to have been a budding piano virtuoso in his youth, having started lessons when he was five, and had accompanied cellist Jacqueline du Pré (through whom he eventually met Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor).2 An alumni of Interlochen, where he spent a summer playing bassoon, he later became a donor to the academy, sponsoring one student’s tuition at Juilliard after encouraging her to apply. There was also the question of a $165,000 Ettore Soffritti cello that he had purchased in 2010 for a cellist named Yoed Nir.

(Nir returned the instrument to Epstein’s estate in October 2019; it was eventually acquired by a firm called Musikhaus, with plans to sell NFTs of the “Epstein Cello.” However, the NFT launched shortly after Ghislaine Maxwell’s conviction. It was removed from Musikhaus’s website, though its founder hoped to relist it eventually.3 The company’s website is now down and they haven’t posted to Instagram since January, 2022. A highlighted Story still lists the instrument as an upcoming token.)

These engagements between Epstein and music were about building up both his performative authority and a moral smokescreen. His email exchange with Kuhn accomplished both. The irony just underneath the surface, however, is Flinstonian. What is more authoritative or ethical than Beethoven, that beacon of Enlightenment humanism whose music is the soundtrack to self-determination and human dignity? And what is more of a Bourdieuian wet dream than a millionaire financier invoking his deep connection to Beethoven in one email while simultaneously orchestrating a sex-trafficking conspiracy in another?4

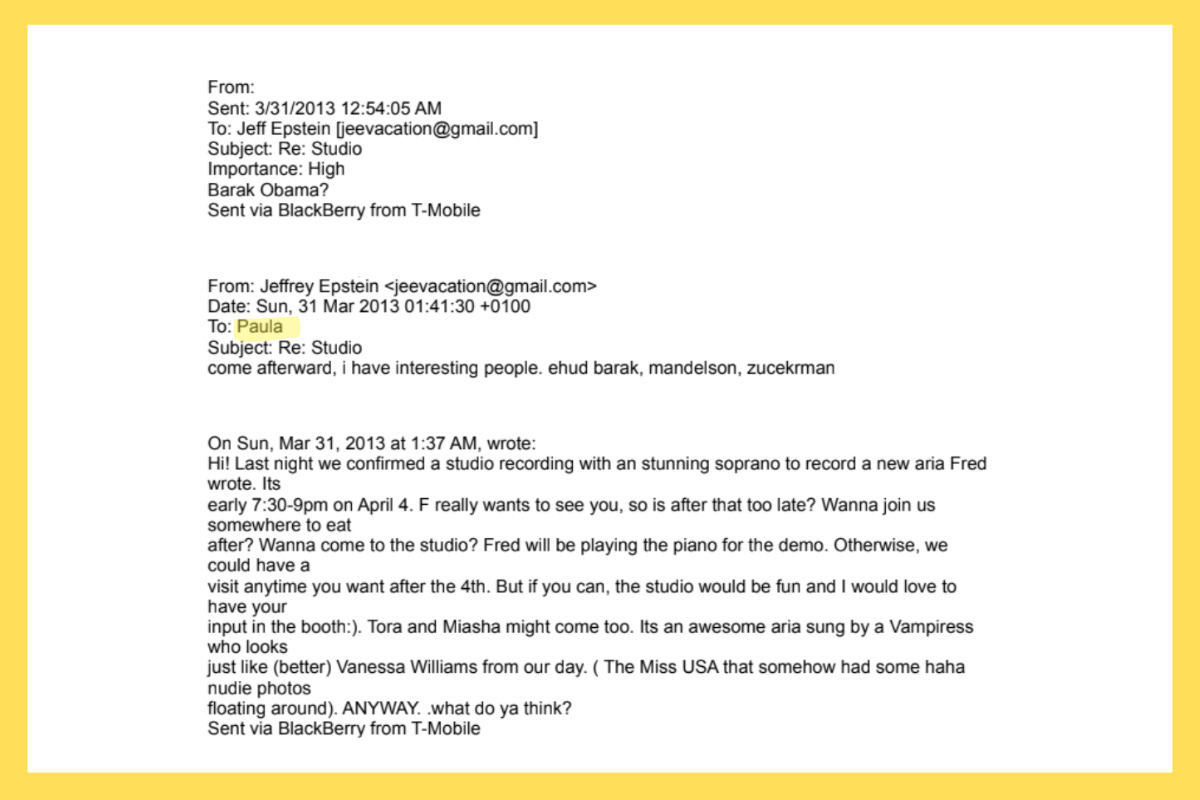

Perhaps even more telling about Epstein’s real connection to music, however, is another email from this latest Epstein document dump. Among his former romantic partners is Paula Heil Fisher, a onetime associate at Bear Stearns who pivoted into opera. Among her notable output in this area was directing the 2004 documentary Finding Eléazar, which followed tenor Neil Shicoff as he prepared to sing the role of Eléazar in Halévy’s grand opera La Juive. She also has written two operas with Frédéric Chaslin — one based on Wuthering Heights, the other an adaptation of Théophile Gautier’s La Morte Amoureuse (about a priest who falls in love with a female vampire) titled Clarimonde.

In 2013, an email exchange with a woman identified only as Paula begins with an invitation to Epstein:

“Last night we confirmed a studio recording with an stunning soprano to record a new aria Fred wrote. Its early 7:30-9pm on April 4. F really wants to see you, so is after that too late? Wanna join us somewhere to eat after? Wanna come to the studio? Fred will be playing the piano for the demo. Otherwise, we could have a visit anytime you want after the 4th. But if you can, the studio would be fun and I would love to have your input in the booth:).”

This would align with the period of time during which Fisher and Chaslin were working on Clarimonde, which was workshopped by On Site Opera in 2014. The other detail provided would also suggest that the soprano being discussed is Alyson Cambridge, who sang the title role in 2014:

“Its an awesome aria sung by a Vampiress who looks just like (better) Vanessa Williams from our day. (The Miss USA that somehow had some haha nudie photos floating around).”

In the tradition of no ethical consumption under capitalism, it’s hard to find clean money in the arts — just ask any museum that used to have a Sackler wing or gallery. In truth, Epstein wasn’t much different. The cello he purchased for Yoed Nir? Nir is the son-in-law of former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak (who is also, as it happens, namechecked in the email exchange with Paula). The musician whose tuition he paid at Juilliard? Her name is Melissa Solomon, and Epstein cut her off after she turned down an invitation to a party with the former Prince Andrew.

In the end, the investments Epstein was making weren’t in music. They were in the complicitous silence. Art either bought him more of that silence, or it gave him something (or someone) to focus on under the plausible deniability of that silence. Amy Davidson Sorkin touched on this in 2019 for The New Yorker when she questioned how Epstein was able, for years, “to operate and be fêted in the social, financial, and academic worlds, despite barely bothering to conceal his illicit activities.” It wasn’t, she argued, “simply a matter of bystanders focusing only on the dollar amount and not seeing the rest.”

Sorkin is right — it goes beyond the dollar amount. To riff on James Carville, it’s the cultural economy, stupid. Epstein’s repertoire of cultural gestures, from financial support to philosophical observations, operated to that effect and bought him the plausible deniability that so many other patrons have been granted throughout history. They bought him the silence. That rest at the start of Beethoven’s Fifth, the silent beat that Epstein insisted “changes the whole dynamic” is an indictment of the world that enabled him. Silence — institutional, social, and cultural — shaped the dynamic of Epstein’s ascent. It wasn’t the notes that protected him. It was the silence that surrounded them.

I don’t understand the significance of the numbers but I feel like this is probably low on the list of questions we all have about the Epstein files.

The New York Times later debunked this story: “Mr. Epstein later took piano lessons, but he never achieved more than a high-school level of proficiency.”

“So what if Jeffrey owned it?” founder Julian Hersh told the New York Times in 2022. “It’s still one of the best 20th-century cellos in the world.”

I can’t help but think of Fidelio in this context, particularly Edward Said’s assessment that it is “the one opera in the repertory that has the power to sway audiences even when it is indifferently performed. Yet it is a highly problematic work whose triumphant conclusion and the impression it is designed to convey of goodness winning out over evil do not go to the heart of what Beethoven was grappling with.”

Do you really think - although the article doesn’t really explore this aspect, but I’m curious - that Epstein listened to Beethoven? Let alone liked his music? Or was his musical and art appreciation an aspect of his act, as a Beethoven fan, I can’t imagine that whatever appreciation of Beethoven was genuine on his part.

What about Leon Botstein and his interaction with Epstein?