9.5 Theses on Art and Politics

The ethics of pursuing classical music in a world on fire.

1. The ethics of pursuing classical music in a world on fire

“What are the ethics of pursuing classical music in a world on fire?” reads a recent Instagram post from one of my new favorite accounts, @teatroallaflopera. “What are the ethical ramifications of pursuing a career within an industry that is quite comfortable creating ‘art’ — work that is beautiful, but routinely avoids confronting the current state of the world?”

The obvious answer is that art is not a form of avoidance. “Beauty,” writes Andre Bréton, “consists of jolts and shocks, many of which do not have much importance, but which we know are destined to produce one Shock, which does…Beauty will be convulsive, or will not be at all.”

Where we’ve lost the thread is in the capacity for convulsive beauty. The problem, as Flopera points out, isn’t with the art: It’s with the institutions that have become gatekeepers of that art.

This came to mind last week when I received a PR email for a new album of works by Ernest Chausson and Germaine Tailleferre:

“On July 14, 1789, the storming of the Bastille became a key symbol of revolution, freedom, and change in France. Today, nearly 236 years later, we reflect on this historic event and celebrate [REDACTED’S] newest release […] an expressive homage to French music’s legacy, available today. Click here to stream on all platforms, and here to read the press release.”

Chausson was a composer of the Belle Époque era. Tailleferre was the sole female member of Les Six (and a contemporary of Breton’s). Neither composer had anything to do with the French Revolution. Their works, though objectively beautiful, have no connection to the Revolution. Indeed, the work representing Chausson on this album (his Concert for Violin, Piano, and String Quartet), premiered in Brussels and led the composer to write: “I must believe that my music is made for Belgians above all.” Tailleferre’s own revolutionary instincts were more apparent (in 1968 she joined the French Communist Party in solidarity with the student movement), but none of that is reflected.

I get that classical music is not an easy sell in 2025. Nothing is. But it seems to me that its sellability is moot if we denude it of its jolts and shocks, repackaging revolution to make it marketable.

2. We don’t remember Tosca for her performance

A tweet I think about a lot, from Gabes Torres in 2021: “May I love in ways that devastatingly disrupt organized state violence.”

It reminds me of a line from another author, Alison Kinney: “Tosca doesn't wait for God to answer: She stabs the chief of police to death.”

Puccini’s heroine is herself an artist, who literally stops the show with the aria “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore” — a credo that I’ve heard more than one person quote as their own way of absolving political engagement. Yet Tosca sings these words while in the vortex of organized state violence: Her lover, Mario (also an artist), has been arrested and is in the middle of being tortured. Scarpia, the chief of police, has just sexually coerced her into saving Mario’s life.

I lived for art, I lived for love, she sings, confused and bereft. I never harmed a living soul…I donated jewels to the Madonna’s mantle, and offered songs to the heavens so that both may shine with greater beauty. So why, oh God, in this hour of grief, do you reward me thus?

And here is where Tosca realizes both the limitations of and convulsions of beauty. She must fight fire with fire. So she doesn’t wait for God to answer her plea; she stabs the chief of police to death. We can argue she does this out of love; love for Mario and love for herself, an act of self-preservation when faced with an impossible situation brought on by state violence. But it’s also an outpouring of Tosca’s art as a singer, so much so that it spills out of its frame and crosses over into real life. It’s the act we remember her for the most. Who’s to say that is also not an extension of her art?

3. Cultural versus contextual literacy

Whenever someone argues that Figaro should just be Figaro without trying to make it about politics, I go back to Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism: “Much of the passionate controversy about ‘cultural literacy’ in the United States and Europe was about what should be read…not about how they should be read.”

In the near-150 years since Beethoven’s death, we’ve become more and more reliant on canon in classical music and opera, turning more towards works of the past than focusing on the present.

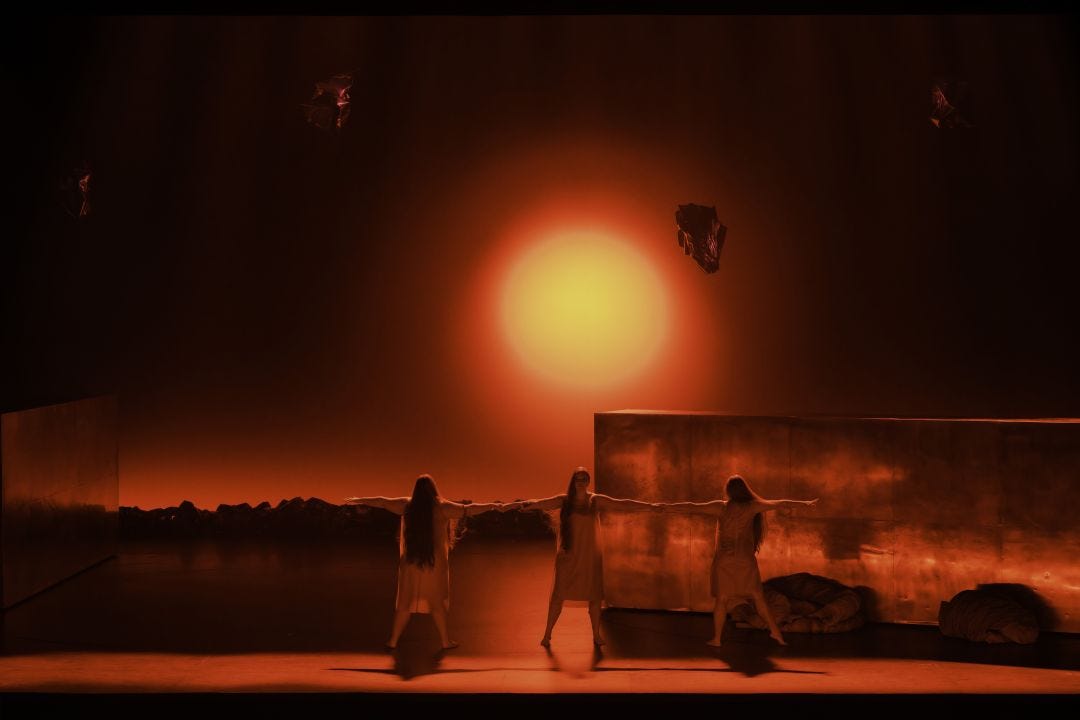

Over time, the political burnish of many operas has dulled, even in the most glaring contexts. Peter Sellars knew this when he set Figaro in Trump Tower 37 years ago. (To quote another Sellars opera: “This is prophetic.”) I would argue that this dulling was hurried along by the private, Gilded Age patrons who built the Metropolitan Opera and the constructed Arcadia of Lincoln Center, dominated by the Met and decades of mostly lobotomized, storybook productions.

Arcadia had been linked to opera and the genre’s formation in Renaissance Italy. The obsession with this Ancient Greek Eden continued throughout history, with Friedrich von Schiller (the playwright behind many operas, including five by Verdi) declaring that the Arcadians “by living close to nature, were naive geniuses who lived better lives than we do and created better works of art because of their ability to maintain a natural state of honesty, simplicity, and virtue that innately worked within the forms of nature.”

I wonder how Schiller reconciled that image of noblesse sauvage with the one Ovid presents of Arcadian King Lycaon cooking and serving his own son to Zeus. It reminds me of how John D. Rockefeller III described the then-nascent plans for Lincoln Center as a “symbol of American cultural maturity, affirming for people everywhere our faith in the life of the spirit,” right before developers for the Center razed San Juan Hill.

4. You can’t practice convulsive beauty in a system that rewards docile obedience

More directors today are reading canonical works in context. The problem with many of these productions is that they still have to work within these larger institutional dictates.

In Kirill Serebrennikov’s recent staging of Don Giovanni for the Komische Oper, the opening to the dinner scene played out as written in Mozart’s score. This includes a mashup of popular opera tunes from the era of the work’s premiere with samples of Martin y Soler’s Una Cosa Rara (which also featured a libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte) and Mozart’s own Le nozze di Figaro. Serebrennikov extended the throughline, inserting a moment from Don Giovanni that had been cut from this production: Don Ottavio’s second aria, “Il mio tesoro.” Here, the supertitles note that this aria had been cut from the performance, due to the Berlin Senate’s cultural austerity measures.

Even before Donald Trump crowned himself, Napoleon-style, director of the Kennedy Center, such a direct call-out from an American opera company would have been unthinkable. Jokes about tight budgets can of course be found (especially in scrappier, more DIY productions), but rarely do they go after the cause versus the symptom. More often, they’re made in the vein of, “Isn’t it funny how much money these companies or composers expect to have for what is, in the end, a trifle?”

They are, in a way, more lip service to the billionaire and multimillionaire donors who deign to underwrite such productions. And it makes a fiscal sort of sense: Why risk a funding loss that could shutter your entire organization if your art speaks the wrong truth to the wrong power? On the other hand, what do we gain from an opera about an F-16 fighter pilot that was originally linked to sponsorship from General Dynamics, especially one that — in the words of Times critic Zach Woolfe — “seems to say that war is OK; there are just better and worse — more and less authentic — ways of waging it”?

Woolfe is also one of the sharper critics in this arena. “What does a single aria cost compared to a lavish new production by an overrated director with a bloated staff of co-assistants?” complained one reviewer of Serebrennikov’s “Il mio tesoro” jab in Don Giovanni, missing both the joke and the deeper truth it barely concealed.

5. Context is also selective

Among the many protests against Berlin’s cultural funding cuts came one in last November, which featured the Deutsche Oper Berlin’s chorus singing Nabucco’s chorus of Judean exiles, “Va pensiero.” It was, in that context, a warning of how the city’s arts sector may too become a homeland “so beautiful and so lost.”

This, roughly a month after the Berlin Staatsoper had debuted a new production of the same work — with more politically-muddied waters.

This, at a time where the majority of artists in Berlin were afraid to express solidarity with or even sympathy for the 2 million Gazans facing over a year of active genocide; at a time where those who did faced professional and personal repercussions.

This, also at a time where even peaceful protests in the city — fully compliant with demonstration regulations and often featuring Jewish groups as co-organizers — were being brutally broken up by the police.

This, with many still failing to see that the future of civil protest, as well as the preservation of both human rights and culture, was interconnected, interdependent. The cultural protests were beautiful. The Palestinian protests were savage.

“Va pensiero” is a piece that has become a political shorthand in the world of opera. But in that moment, that shorthand was illegible, nonsensical.

6. Philanthropy has become a form of plausible deniability

Consider a person who grows up in the orbit of an authoritarian autocrat (one known equally for his human rights abuses and his extravagant lifestyle as his people suffered poverty and hunger).

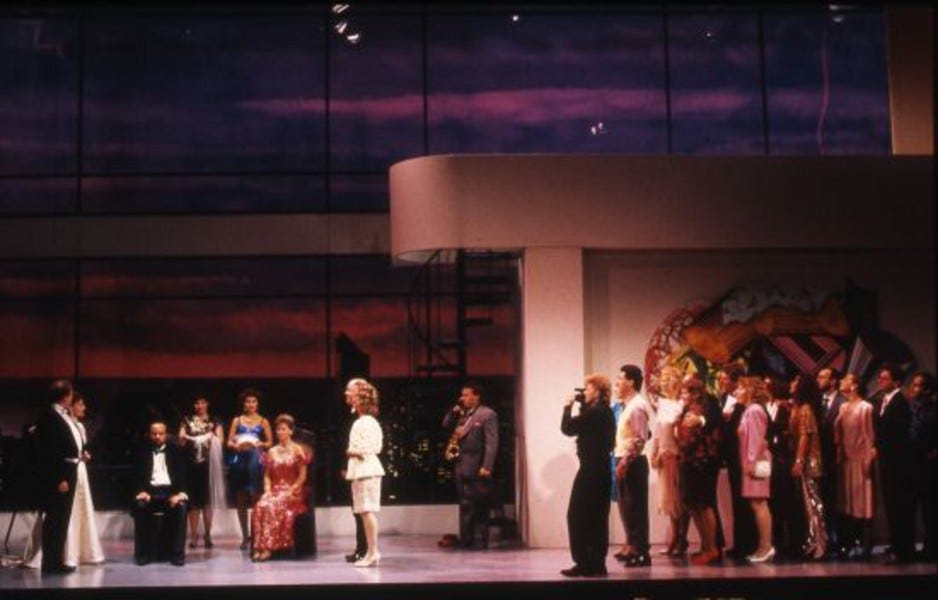

She moves to the United States, marries first an ambassador who works with both the Nixon and Ford administrations then — after a scandalous society-pages affair — a Texan billionaire. She makes a $25 million gift to the Metropolitan Opera, which names its Grand Tier in her honor and features her in the Café Momus scene in a performance of La Bohème (where she is cheered on from her box by Henry Kissinger). About a decade later, in 2015, she’s elected acting chair of Carnegie Hall.

In 2016, she is also just one of two large donors from Texas who directly supports Donald Trump’s first presidential run (amid support for many other Republican candidates in that year and before). The year before, she had underwritten a new production of Le nozze di Figaro for the Met, set — ambiguously — in “1930s” Spain.

Is this before the war? During the war? No reference is made to the political events of this pointed decade in Spanish history. Perhaps that’s just as well: It was under General Franco’s dictatorship that bilateral relations were reestablished with Iran under Mohammad Reza Shah. It might have been a step too far to link this production of one of Mozart’s most class- and politically-conscious operas, however obliquely, to the Shah — who, through marriage, became Mercedes Bass’s step-cousin-in-law. And anyway, what does that matter next to “Sull’aria”?

This isn’t a standalone example, as both Ben Davis and the Sackler family have, in contrasting ways, pointed out. And yet we still expect art to save humanity, even as those financing humanity’s undoing are also underwriting

7. The message is the medium

And given all of that, what does it say when the same opera house with a floor named for a bankroller of modern fascism will open its next season with a new opera about two brothers attempting to fight last century’s fascism?

An opera about, in the words of the production’s director, “the kind of challenges you face when we’re experiencing genuine oppression and how we respond to it”; about using art as a way of working through and subverting that oppression?

Would Kissinger sit on his hands during such a performance? Or would he have applauded as the point sailed over his butcherous little head?

8. The medium can also massage

Around the time that Verdi’s Macbeth premiered in 1847, Italian nationalist poet Giuseppe Giusti wrote to the composer in an attempt to steer him away from Shakespearean themes and back towards works that spoke more directly to the fight for Italian statehood and self-determination:

“You know that it is the chord of sorrow which finds the readiest echo in our breasts. Sorrow, however, assumes different aspects depending on the time and nature and condition of this or that nation. The kind of sorrow that now fills the minds of us Italians is the sorrow of a race that feels the need of a better destiny, the sorrow of one who has fallen and wishes to rise, the sorrow of one who repents and waits, longing for regeneration. Accompany, my Verdi, this high and solemn sorrow with your noble harmonies. Do what you can to nourish it, to strengthen it and direct it to its goal.”

I wonder if this letter was written before or after Giusti had heard Macbeth, particularly the opening of Act IV when a chorus of Scottish refugees sing of their “Patria oppressa” — an addition to the libretto that doesn’t have a direct corollary in the Shakespeare source. My guess is that he hadn’t.

Nonetheless, as 1847 moved into the revolutionary year of 1848, Verdi did return to more explicitly political themes with La battaglia di Legnano, his most overtly-Risorgimentified work and one that Charles Osborne considers to be his most propagandistic around the fight for Italian unification. It wasn’t seen in the United States until 1976, and — apart from some recent activity around the anniversary of Italian unification and the Verdi bicentennial — is rarely heard, especially compared to Macbeth or Nabucco.

Yet even Verdi’s most lyrical, most musically beautiful works — many written after the Risorgimento — can’t shake meaning and metaphor. What is La traviata if not a social critique on class, sex, and gender? What is Rigoletto if not a cautionary tale against absolute power and impunity? What is Aida if not both an argument against and a byproduct of imperialism? And many of these works were still not spared censorship: Rigoletto had to move the action from the world of France’s King Francis I (yes, that Francis I) to the court of the Gonzaga family in provincial Mantova. Likewise, Verdi couldn’t portray regicide in 18th-century Sweden with Un ballo in maschera, and had initially recast the work in colonial Boston as a workaround.

Perhaps these changes defanged these works at the time of their premieres, but with the benefit of hindsight we can read them more clearly — and locate within them the chords of sorrow they struck — and can still strike today.

9. Art doesn’t make a difference…

“Do protest songs actually make a difference?” BBC journalist Amol Rajan asks Billy Bragg. Bragg’s response is immediate and categorical: “No.”

“It would be much easier, wouldn’t it, if all you had to do to make the world a better place is buy Billy Bragg records, and come to his gigs, and applaud him when he sings ‘There Is Power in a Union,’” Bragg adds. But music — and, he adds, art at large — has no agency.

This is accurate: Art is an abstract concept, one that we apply to endless works and media with very little consensus. Is John Cage’s 4’33” art? (Maybe not if you’re John McWhorter.) What about Tumblr? (Maybe so if you’re Hrag Vartanian — and in a world full of John McWhorters I find it is always advantageous to be a Hrag Vartanian.)

Likewise, we apply a similar form of both plug-pulling and extended-life-support to the authors of said art. The aborted world premiere of Das Floß der Medusa ended Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s friendship with the oratorio’s composer, Hans Werner Henze — Henze’s Marxist awakening and revolutionary ideals offended Fischer-Dieskau, who had witnessed firsthand the terrors of the Red Army in post-war Berlin. At the same time, Fischer-Dieskau was able to set aside his feelings towards Wagner, his antisemitism, and his own family’s cult of personality within the Nazi Party, and sing many of the composer’s roles.

That’s not an indictment of FiDi, but rather an indication of how easily inconsistent we are with which artists. It’s also worth noting that Henze’s Medusa is an exception to a truism posited by Frederic Rzewski in 1983 that “the kind of art which satisfies the political world is often pretty feeble art.”

9.5. …until it does

Despite this, Rzewski adds: “An effective combination of the two is nonetheless theoretically possible, perhaps because it is practically necessary; a condition that may exist only in certain moments of history.”

We are at a certain moment of history. Having said his piece on art having no agency for BBC Radio 4, Billy Bragg then describes the power he literally feels in a union when, after performing his signature anthem, he is re-activated by the crowd, his cynicism temporarily dulled.

In following Zohran Mamdani’s campaign as an old New Yorker, I was pleasantly surprised to realize that his wife was the Syrian-American artist Rama Duwaji, whose work I had first come to know in 2019. In 2020, in the wake of the Beirut port explosion, Duwaji offered to do a custom illustration for anyone who donated $100 or more to the Lebanese Red Cross. My own Syrian grandmother died a few days after the explosion, and I was eager to take Duwaji up on her offer.

“Is it all right if I give you some stories about her in addition to some photos?” I asked and Duwaji happily accepted some of the anecdotes my grandmother told me about barely surviving to escape Syria as a child during the Ottoman Siege. What she sent me back was fully my grandmother. A representation rather than a replication.

As the polls were closing for the mayoral rankings in New York, the actor Morgan Spector (who, not incidentally, plays a robber-baron-cum-Met-Opera-patron on The Gilded Age) wrote, “If you think that politics should be the instrument we use to collectively provide for each other’s needs, vote for Zohran. If you think it should and could be the space in which we democratically imagine an inclusive vision of the future, vote for Zohran.”

The capacity for art doesn’t guarantee anything in a politician, obviously. But what stuck me in Spector’s comments was how art is among the divining tools for our vision of the future — and how much art can be contained within that vision. At its best, art is a collective provision. How beautiful — how shockingly, joltingly beautiful — to imagine a New York where the mayor is the son of a filmmaker and husband of a visual artist. How convulsively revolutionary.

Absolutely brilliant.

terrific